Though the first genetically modified organism (GMO) patent was issued over 30 years ago, the landscape is still clouded with questions. Is a federal labeling mandate off the table? Is organic always non-GMO? What about “all-natural” products? Here, we’ll go through the most pressing questions – and answers.

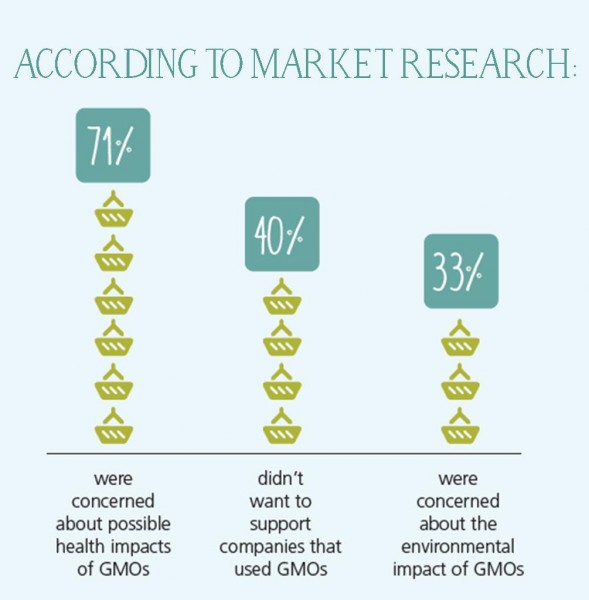

Non-GMO activists have a variety of concerns in their arsenal – and many of them resonate with natural and organic shoppers.

Though the jury is still out on any health issues directly coorelated with GMO consumption, many GMOs are engineered to resist typical pesticides and herbicides. This is concerning to some because studies suggest pesticide resistance can actually increase the use of chemical pesticides and herbicides, which threatens ecosystems and potentially human health. Many are also concerned about the socioeconomic implications of a few large biotechnology companies controlling patents on seeds and crops. Because these companies hold patents, they’re legally allowed to take action when inevitable drift occurs onto neighboring fields. Between patent infringement, crop-damaging superbugs and increase use of chemical products, who pays the price? Often, it’s local farmers and communities.

GMO stands for genetically modified organism. Crops that are GMOs are also often called genetically engineered. This means that a company has taken genetic properties of one plant and artificially transmitted them into another one. Often, the goal is to develop a plant superior in its ability to ward off pests. The Non-GMO Project Verification and the newly launched NSF Non-GMO True North certification prohibit the use of GMOs in a product.

USDA Organic standards dictate that any food carrying the organic label must also be GMO-free. But to meet the organic standard, food companies must also prove their fruits and veggies are grown without synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, sewage sludge or ionizing radiation. Farmers must prove their livestock and animals are raised without antibiotics, growth hormones, or non-organic feed.

In other words, all organic food is GMO-free. Not all GMO-free food is organic.

No, and therein lies the great debate. Activists believe that consumers have the right to know whether their foods contain GMOs. GMO companies believe that there is an undue stigma attached to genetically engineered foods, and that business would suffer should such labeling become mandatory. Over 60 countries, however, such as the European Union, require that food products containing GMOs must indicate which ingredients are genetically engineered on the package. While voluntary labeling deals like the Non-GMO Project and the newly launched NSF Non-GMO True North allow brands to communicate to consumers that products are GMO-free, manufacturers are not required by law to label GMOs.

In July of this year, the House Agriculture Committee passed the Safe and Accurtate Food Labeling Act. Biotech was thrilled, Non-GMO groups were less than thrilled.

This bill forces companies who want to release a new GMO into the market to first receive federal safety approval. It also establishes a voluntary nationwide labeling program – note that this bill did not make labeling mandatory. While some states (like Maine, Vermont and Connecticut) have mandatory GMO labeling laws on the books, this act deprives states the right to require GMO labeling. Proponents of GMO labeling maintain that this law is not enough to satiate the public’s desire for transparency.

It’s undeniable that consumer interest in GMOs is growing. And while a big chunk of shoppers are avoiding or reducing GMOs in their diet (the Hartman Group estimates this be about 40 percent of all shoppers) their motivations vary significantly.

It’s undeniable that consumer interest in GMOs is growing. And while a big chunk of shoppers are avoiding or reducing GMOs in their diet (the Hartman Group estimates this be about 40 percent of all shoppers) their motivations vary significantly.

There’s still room for education. A little less than half of the consumers surveyed still didn’t understand exactly what GMOs are – but nearly half expressed that they wanted to know exactly what’s in their food.